In 1964, Duke Ellington approached Bunny Briggs, the great tap-dancer who died just before Thanksgiving at the age of 92, with an idea for a special project he was working on. The pre-eminent American composer-bandleader described it as a “Concert of Sacred Music,” which was a highly radical idea.

Fifty years ago, even the notion of jazz orchestras playing any place but ballrooms and gin joints was still a relatively new one, and for jazz musicians to perform in a church setting was unprecedented. Jazz was still associated with bootleg liquor and loose morality, but Ellington wanted to achieve the dual purpose of cleaning up the music’s reputation and expressing his own ecumenical emotions. There was only one dancer in the world who could deliver that combination of reverence and joyful abandon that Ellington wanted, who could fully represent the African-American vernacular dance form in the same way that Ellington and his orchestra were representing jazz, who could simultaneously make religion fun and make fun into something undeniably spiritual.

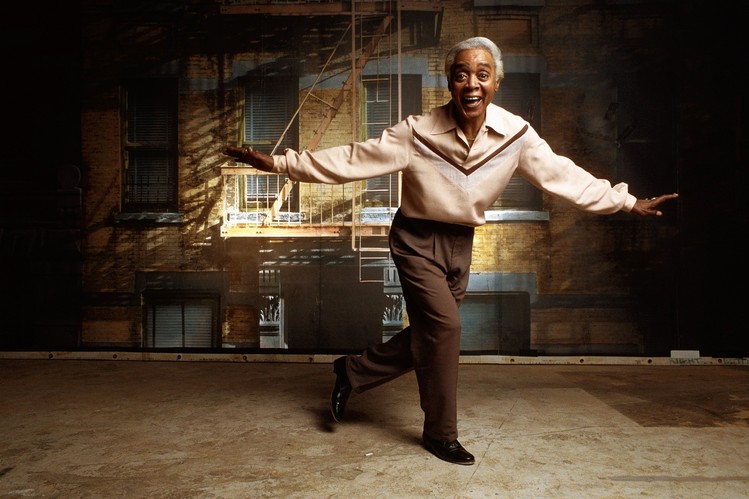

Ellington, who introduces Briggs at the work’s premiere (which took place at San Francisco’s Grace Cathedral on Sept. 16, 1965 and was thankfully filmed for posterity and released on DVD in 2005) as “the most superleviathonic, rhythmaturgically-syncopated tapsthamaticianisamist,” could have never found a better dancer to portray David in his mythic offering to the Lord. Briggs hoofs it at once with humility and supreme confidence while the Herman McCoy Singers, vocal soloist Jon Hendricks and the entire Ellington band wail behind him. He dances without hesitation or pause for the entire nine minutes—in this respect Briggs reminds us of one of Ellington’s great marathon soloists, in particular tenor saxophonist Paul Gonsalves, in that he can keep improvising tirelessly without his energy and invention ever flagging. In an undated online presentation about tap-dancing produced by the Joy2Learn Foundation, Gregory Hines, who died in 2003, says that Briggs could dance for 45 minutes straight—a whole set as a single dance—and Briggs himself credited the success of his performance in the First Sacred Concert to divine inspiration.

It was hardly the first time Briggs had radicalized tap-dancing by bringing it into a bold new setting. In the mid- to late 1940s, the dancer—who had been born Bernard Briggs in Harlem in 1922 and nicknamed Bunny early on because of his impressive speed—became to tap-dancing roughly what Ella Fitzgerald was to scat singing. He was the first to take an existing, specific form of expression and update it for the new musical language that was then known as bebop. There’s a short 1950 film—in which Briggs appears in the company of two progressive swing veterans, Nat King Cole and Benny Carter—wherein his routine is only two minutes long but gives a clear impression of everything that he can do. Briggs enters to an exciting, dissonant fanfare reminiscent of Dizzy Gillespie, which is a sign that he’s already incorporated the musical vocabulary of modern jazz into his dance routines, and throughout he works mainly to a bop-era rhythm section of piano, bass and drums in a super-fast tempo that is, again, thoroughly boppish.

What testifies more than anything to Briggs’s special brilliance is what might be called his dancer’s sense of dynamics, not only conveying the difference between loud and soft, as a horn player might, but between small intimate gestures and big dramatic ones.

At points he flails his arms and legs so far into the air that you can’t believe those limbs remain attached to his body. At other moments he does some of his most effective dancing without appearing to be moving at all—he seems to travel across the stage while hovering slightly above it, his feet apparently vibrating so fast you can’t even see them move; he looks like he’s traveling by conveyor belt. Yet, with the tap noise seeming to come from nowhere, this is the loudest part of the dance—the taps never stopping, the beat never missed. Then Briggs reverses the polarities, doing some of his most vivid, broadest gesturing without making a noise. How does he do it? What magical sleight-of-hand or, rather, sleight-of-foot was involved? Did he somehow attach a muffler to his tap shoes while we weren’t looking?

He generally directs our attention not with his feet but with his eyes; when he gazes down at the end of his graceful legs, we look too. At one point he looks dead ahead even while swaying dramatically from side to side as if on a boat in a storm. He also does one of his signature moves, adjusting the lapels of his coat as if it were starting to snow and then sliding across the stage in a skating motion that resonates so vividly you can practically see the ice.

Briggs made other films—starting with an appearance in a Stepin Fetchit short at the age of 9 or 10, offering about 50 seconds of ace buck-and-wing to “Happy as the Day Is Long.” There’s also a 1949 short with Charlie Barnet’s orchestra in which he transcends the somewhat demeaning garb of a telegraph boy. He also recorded with Barnet, and was very convincing in the aural-only medium, as both a scat singer and a blues singer.

He not only was able to convey spiritual devotion as well as an ineffable sense of modernism, as we have seen, but in 1989 I saw him depict the full gamut of emotions, from elation to heartbreak, in a five-minute solo in the Broadway revue “Black and Blue,” once again using an Ellington tune (“In a Sentimental Mood”) as conduit. Thankfully, a YouTube video exists to confirm my memories. He was pushing 70 at that point, but, at his greatest, which he always was, Bunny Briggs made time stand still.

Mr. Friedwald writes the weekly Jazz Scene column for the Journal.